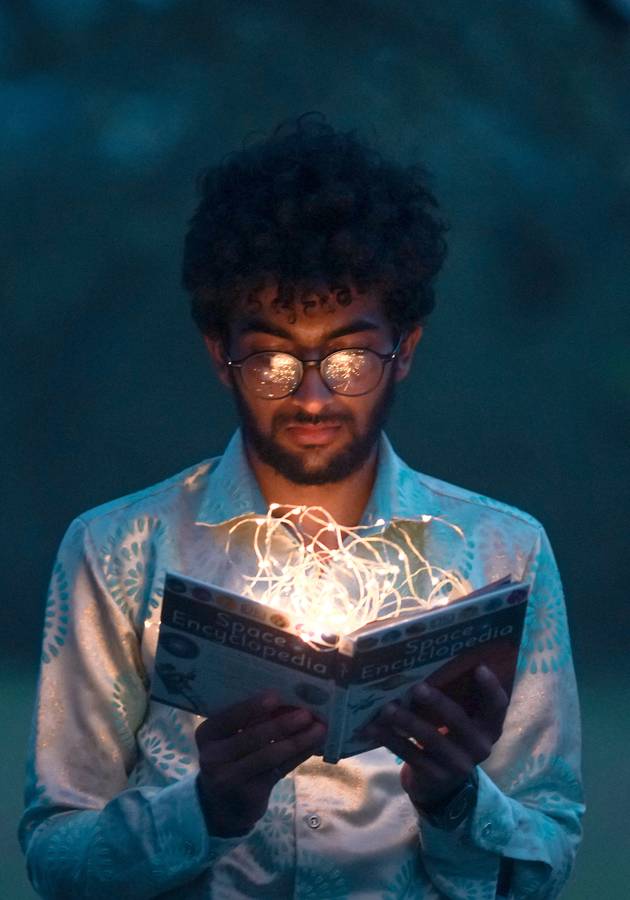

Before modern technology made acquiring information exceptionally easy, there were only a few places where you could do that properly: the classroom, the laboratory, the workshop, the library – and maybe a few others. Your room was certainly not one of them: just until recently, there was no Wikipedia, and the best encyclopedias around were rarely updated, spanned some 30 volumes, and could be afforded only by well-off institutions.

“It almost feels like the dark ages when you realize how difficult it was to simply acquire knowledge and learn about what you’re interested in,” Peter Hollins expresses his disbelief at the beginning of “The Science of Self-Learning.” Less than 200 pages long and printed with quite a large font, Hollins’ book may seem like something assembled rather quickly, but don’t get fooled – there’s a lot you can take away from it.

So, prepare to do just that: get ready to learn how to learn and save yourself countless hours of wasted effort and never-ending headaches!

The principles and history of self-learning

The process of acquiring information has changed significantly over the last few decades. What hasn’t changed, however, is the educational system: it is still based on the traditional top-down model of learning. The problem? Well, this means that, by definition, you still learn what somebody else has decided beforehand that you should – be that someone your family, your private instructor, or, in most cases, a school board. Not that this is necessarily bad, but it was always too restrictive. And now, it is outmoded as well.

Mark Twain, Benjamin Franklin, and Albert Einstein – to mention only a few – knew this long before the advent of the internet. All three of them were autodidacts: namely, people fully or partially self-taught in the arts and sciences they eventually mastered. They weren’t the only ones, though: you’d be surprised to hear how many of your idols were nothing more than curious individuals who learned almost everything they knew all by themselves. To mention only a few: authors such as Hesse, Steinbeck and Tagore, musicians like Bowie, Cobain and Hendrix, movie directors such as Tarantino, Kubrick and Welles, and even inventors like Da Vinci and Tesla were all just that – autodidacts.

So, self-learning is not a new pursuit; what’s new is how attainable modern technology has made it. “Courtesy of the internet, the world is your oyster,” cries out Hollins, “and we have the ability to learn anything we want these days!” But before we can do that, it’s important to first understand the natural mindset of the autodidact – the mental state that makes self-learning possible.

The learning success pyramid

Traditional learning is nothing more but a mixture of reading and regurgitation. Self-learning is something more: a process of self-directed growth through reflective intellectual curiosity. Understandably, however, self-learning isn’t a mode operated by a switch that you can just flick on. Before you start educating yourself, you need to “put some mental and emotional groundwork in place to prepare for success.” The learning success pyramid – conceived by educator Susan Kruger – can help you a lot with that.

Kruger attempted to identify “the necessary elements one must bring to ensure accomplishment in learning throughout their life.” After a long process of elimination, she focused on the most essential three: confidence, self-management, and learning. This is how Hollins sums up her findings:

“The learning success pyramid accurately lays out the three aspects of learning, two of which are typically neglected and thus serve as enormous barriers for most people. First, you must have confidence in your ability to learn, otherwise you will grow discouraged and hopeless. Second, you must be able to self-regulate your impulses, be disciplined, and focus when it matters – you can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make him drink. Third comes learning, which is where most people tend to start – to their detriment. Learning is more than picking up a book and reading, at least psychologically.”

Now that you know the basics of self-learning, it’s time we share with you a few techniques to help you on your road to mastery. Learn them, and use them as often as you can – and you’ll be able to get the most out of anything you’d read, hear, or see.

The SQ3R method

Introduced by American educational philosopher and psychologist Francis P. Robinson in his 1948 book “Effective Study,” the SQ3R method is one of the most powerful tools of the modern autodidact. Developed specifically with comprehension in mind, the SQ3R method makes reading a much more active process by creating dynamic engagements between the books and the reader. Its objective is engraving information into the long-term memory of a self-learner. The name of the technique is an acronym of its five components: survey, question, read, recite, review. Let’s have a look at them all.

- Survey. As tempting as the opposite might be, you should only start reading after you’ve surveyed your reading material and acquired a general overview of its content. This should take you no more than five minutes. Go over the contents of your book, take note of its headings and subheadings. Hollins’ analogy brilliantly illustrates the importance of this step: “It’s just like taking a look at the entire map before you set off on a road trip. You may not need all the knowledge at the moment, but understanding everything as a whole and how it fits together will help you with the small details and when you’re in the weeds.”

- Question. Even at the second stage of this method, “you’re still not diving into the deep end.” As suggested by its name, the question stage is the time for inquiries and questions. What kind of questions? Simple, general. You can just ask yourself, “What this chapter is about?” or convert the titles of the book’s headings into questions. This yet another 5-minute phase, equally essential as the first one: it is through these questions that you’ll wake up your curiosity – the defining feature of an autodidact.

- Read. Now you can begin reading – and finally do it the only way it should be done: actively. Equipped with a few questions and a lot of curiosity, thanks to the introductory survey, you should be treading familiar ground by this time. You’ve become a detective, trying to fill in the gaps the first two phases left in your understanding of the book you’re holding.

- Retrieve. The only way to know if you have actually remembered something of the things you’ve read is by testing yourself. So, do that. See how much of what you’ve read you can retrieve from memory. Try to answer your previously raised questions. It is of vital importance to formulate and conceptualize the learned material in your very own words. If it helps, act as if you’re a teacher standing in front of a group of children. Try to explain to them in the simplest words available.

- Review. The final stage of the SQ3R method is reviewing. It’s basically retrieving – after some time. So, after a certain milestone – the end of the day, the closing of the book – repeat back to yourself the main points quickly.

Cornell notes

English philosopher Bertrand Russell said once that there’s not a big difference between reading without taking notes, and not reading at all. So, if you are one of those who don’t want to put any marks on the margin of a page, try to change that about yourself immediately: this might be the reason why you’ve never been able to remember the things you’ve read.

Unfortunately, few people take notes when reading; and even fewer take them in the right manner. Devised by Walter Pauk, an education professor at Cornell, the Cornell note-taking system has been scientifically proven to work wonders in terms of efficiency, tidiness, and memorization. And you need nothing more than a piece of paper to start practicing it today.

It is quite simple. Just divide the list into two unequal columns – the right one about twice the size – and leave about 2 inches (5 cm) at the bottom of the page. Now, in the right column, put your notes; in the left column, put the keywords related to the notes, and a summary of what you’ve learned in the space at the bottom. And that’s it: scientists say that, simply by restructuring your notes this way, you’re helping your mind restructure them as well.

Read faster and retain more

Forget about note-taking: you might be reading wrong as well! There are ways to do it faster and more efficiently. As far as speed-reading goes, take heed of the following four pieces of advice:

- Stop subvocalizing. Subvocalizing is defocusing and slows you down quite a bit.

- Train your eyes. If you want to read faster, you’ve got to train yourself to scan faster. And the best part of your body to start training when it comes to reading is your eyes: the less they slide away from the page, the faster you’ll be able to read.

- Strategically skim. Slow readers read linearly, but fast readers read diagonally. Learn to strategically skim the pages where some marginal topics are discussed or where the main topics are merely being introduced.

- Focus and be attentive.

Reading faster is only a part of the equation. And it’s the least important part. If you want to become an autodidact, you need to learn how to read properly – regardless of your speed. To explain what he means by this, Hollins reminds his readers of Adler and Van Doren’s classic, “How to Read a Book,” and their classification of the four dimensions of reading:

- Elementary: which is how you probably read right now.

- Inspectional: when you start wondering what it is precisely that you’re reading.

- Analytical: when you start taking Cornell notes.

- Syntopical: when you start comparing the acquired information with other books exploring the same topic.

The difference between traditional and self-learning is basically the difference between the first and the other three levels of reading. Becoming an autodidact is all about becoming a syntopical reader. After all, at school, nobody teaches you to start asking questions about what you’re reading; if anything, they teach you the opposite. Autodidacts don’t think that way. They actively search for meaning: both in the texts they read, and, more importantly, in the lives they lead.

Final Notes

“Never judge a book by its cover” may be a cliché, but “The Science of Self-Learning” is proof of why it is worth repeating clichés from time to time.

Though quite casually designed, this self-published book offers just enough to get you on track to becoming an autodidact. More importantly, it isn’t shy at all to reveal many of its sources – so it basically includes a reading list as well.

If you are not a fan of traditional education, here’s a great place to start your research into the art and science of self-learning.

12min Tip

If it ever made sense for people to become self-learners, now is that time. Use modern technological benefits to explore the world around you. Use the SQ3R method and the Cornell note-taking system to read more and remember better.